Everyone can learn to draw.

I not only hear many people say “I can’t draw”, I hear them express how scary it is to try. They really want to learn to draw; it’s an activity millions of people still crave, even in this age of instant images and smartphone cameras. Accepting a long-held myth that drawing is just a “gift” bestowed on the talented few, people just assume that if they’re not “naturally skilled”, then drawing just isn’t not for them. Nonsense.

Some people are good at sports. A select few are professional athletes. Yet millions play in recreation leagues, or with friends for fun. Why can’t drawing be the same? What keeps people from enjoying a little drawing in their lives?

Because drawing was enjoyable from a young age, and I was enthusiastic about getting better and practicing a lot, I never thought about the hurdles most people face when learning to draw. It wasn’t until I started researching the long history of drawing machines and drawing instruments that I began to piece together observations about this simple question: Why do people think they can’t draw, even if they’re scared to try?

First, some clarification. When we talk about “I can’t draw”, I think people mean “I can’t draw well.” And they use “well” to mean “accurately” or “lifelike.” Their goal is to draw accurately from life. Unlike doodles, cartoons, design sketches, electrical diagrams, or the endless ways drawing functions for communication and art, drawing accurately from life is a goal-oriented task with specific, objective scoring: “Here is my drawing of that flower. Does it look like that flower?” A lot is riding on that answer.

If people accepted that drawing accurately from life is hard, and is hard for some fundamental reasons common to every single human, maybe it wouldn’t be so scary to start drawing.

Ready to draw with the NeoLucida? Check out Using the NeoLucida for an overview of how to draw with this nifty little tool.

Drawing Accurately from Life is Hard, Part 1

It’s hard to forget the names of the things we see. Part of the reason it’s hard to draw accurately from life is that we aren’t particularly good at seeing life accurately. Our brains are very efficient and generalize sensory information. We look at someone’s face, our brain tells us we see “face.” It’s convenient shorthand for a lot of visual information.

To draw that face, we need to forget that it’s a face. It’s actually light and shadow, contours, edges, color, texture, all rendered in proportion and in perspectival space. There’s a lot of detail information—hidden behind the associative labels we give things—we need to observe carefully to render it accurately.

People who draw well have trained their brains to see past the names of the things seen, and break it down to useful parts for drawing.

* * * * *

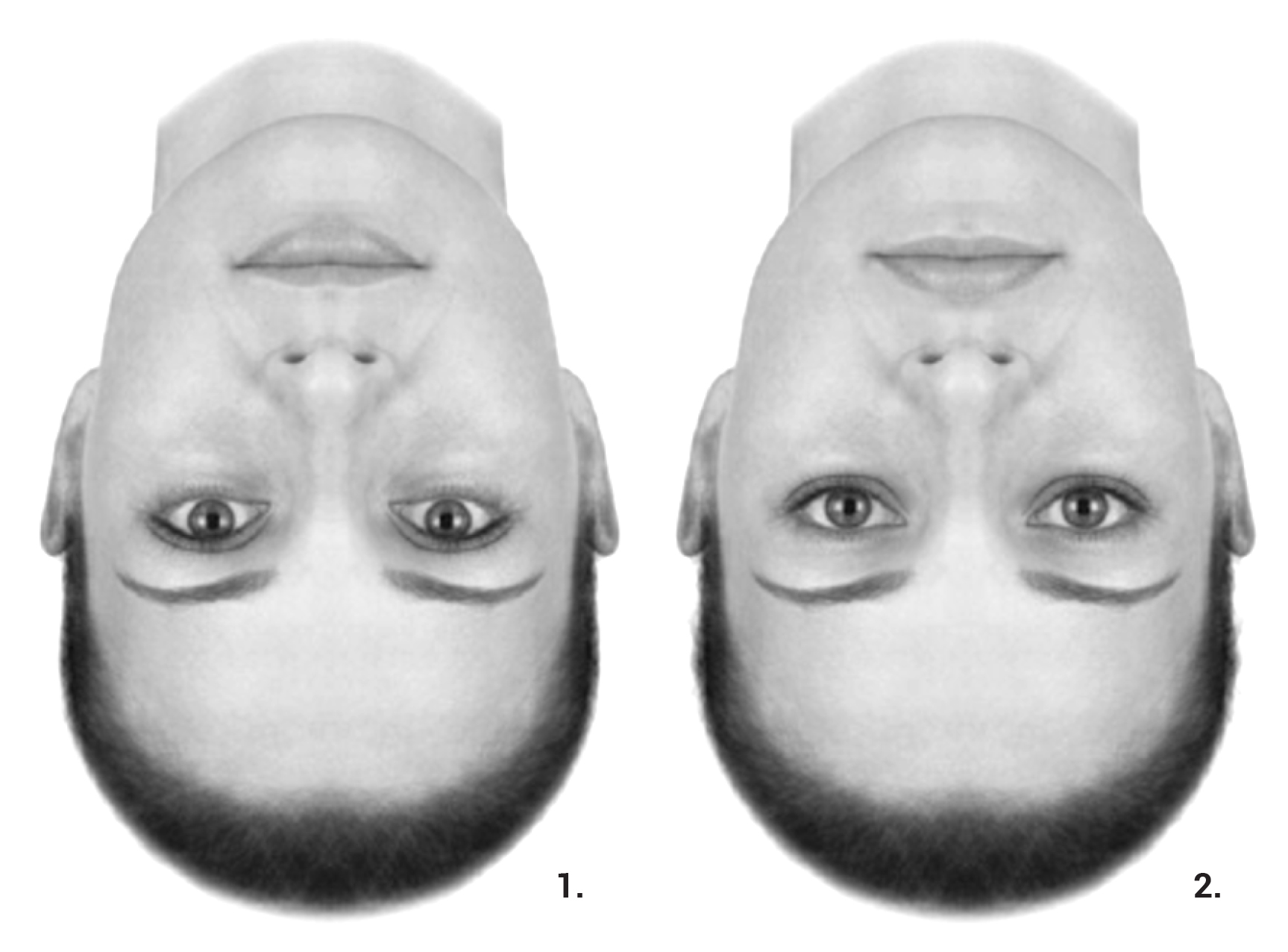

Both of these faces below look perfectly normal. When you turn this page upside-down, it becomes clear face #2 has been manipulated. The eyes and mouth are inverted from normal. When we examine the world, we tend to generalize and miss the specific details of form, light, and proportion. Drawing accurately begins with learning to see the details apart from the whole. Forget what you expect to see and just record what is there. Sounds simple, but you’ve spent a long time listening to your brain and now it’s in the way.

Drawing Accurately from Life is Hard, Part 2

You can’t see your drawing and your subject at the same time. You have to look at a detail—an edge, a curve—of your subject, "memorize" its shape and length, then look away from it to transfer it to your page. When you are looking at your page, you can’t look at your subject to confirm your stroke’s accuracy.

It would be much easier if we could just “lock” your hand movement to your eye movement. Then you could “trace” that detail with your eye—follow the curve of a jawline, a mountain top, a pear in a bowl of fruit—and your hand would just follow. Try it. In drawing classes, we call this a blind contour exercise. It’s great for building hand-eye coordination—not to mention great fun—but it also shows how imprecisely the hand is calibrated to the eye.

Let’s imagine you’ve succeeded in training your eyes to clearly see edges and shapes and the many tiny details that make up your subject. You still have to transfer the vision to the page. And that means looking away from your subject. As soon as you do, you are asking your brain to “carry” that information

The latency between image input and drawing output can be devastating to accurate representation. The memory-image can deteriorate rapidly, being replaced with assumptions or doubt as pencil touches paper.

* * * * *

These two artists illustrate the problem: the artist on the right is looking at the subject. She isn’t looking at her easel, so she isn’t drawing. She is in “input” mode: taking in the contour, the edge, the shape of a detail of her subject. The artist on the left is looking down at her page to guide her pencil. While she does this she has to remember what contour, edge, shape she saw. Over the course of a drawing, this back-and-forth can happen thousands of times. If you’re new to drawing, this could mean thousands of chances for errors.

And it’s exhausting.

Drawing Accurately from Life is Hard, Part 3

Life is in three dimensions. Your page can only hold two. We have built in our brains a very useful and stable notion of three dimensions in space. Each of our eyes sees from a slightly different point of view; our brain takes the discrepancy between each view and translates that as “depth.”

Drawing accurately from life flies in the face of real life. Some techniques for making flat paper hold depth are easy. Drawing an object blocking another implies depth—one thing is closer to you than the other thing. Rendering far-away parts of a scene as lighter due to “atmosphere” is also effective. But these are just tricks that bypass the real challenge.

When drawing from life, you remove a dimension from reality but expect your drawing to convince people that it’s not missing that third dimension. Cutting one dimension—a “dimension-ectomy”—isn’t an intuitive process, since it involves removing an essential part of our everyday lived experience: seeing in 3D.

Cameras, projectors and video screens do an excellent job of flattening three dimensions into two, but they cheat. They use focus to describe depth in the flat plane of a TV. The actor is in focus, the background or foreground objects are out of focus. It’s an effective mechanism we have learned to interpret as depth, but that’s not how our eyes work. That’s not drawing.

* * * * *

Leon Battista Alberti noted that an easy way to understand perspective is to imagine a thin veil between you and your subject “...so the visual pyramid penetrates through the thinness of the veil”, (De Pictura, 1435). The veil “slices” through the imaginary rays connecting your eye and a 3D object, leaving a realistic, flat image of your object. Even 600 years ago, artists knew flattening a subject into two dimensions is hard. Alberti remarked how useful his veil idea is, because “You know how impossible it is to imitate (an object), for it is easier to copy painting than sculpture.”

To wit: 3D to 2D is hard.

Brook Taylor, from New Principles of Linear Perspective, 1719

What if you could simply trace directly from life?

The above challenges have one thing in common: There are built-in gaps in the hand-eye-mind circuit required for drawing. Your mind sees in 3D; it’s hard to turn that off. Your eyes have to do a lot of work moving between drawing and your subject. Your eye and mind are not used to seeing the world as compositions of line, shade, form, and space.

Imagine you have a picture of a flower. If you put a piece of thin, clear glass over it and used a pen to trace the picture, you would get a pretty good drawing of the flower. Why?

It’s already an image; it’s two dimensions.

You are looking at your pen and the subject at the same time.

You are busy tracing an edge, a contour, a boundary between light and dark. No time to think “petal” or “flower.” It’s a line.

The NeoLucida and NeoLucida XL use sharp, undistorted reflections to give you a live image of your subject superimposed on your paper. It is two dimensions, it is in the same view as your hand holding the pen, and it is ready for tracing.

Camera lucidas—and many similar drawing aids throughout history—are effective training tools because they assist your hand, eye, and mind to work together in ways drawing accurately from life requires.