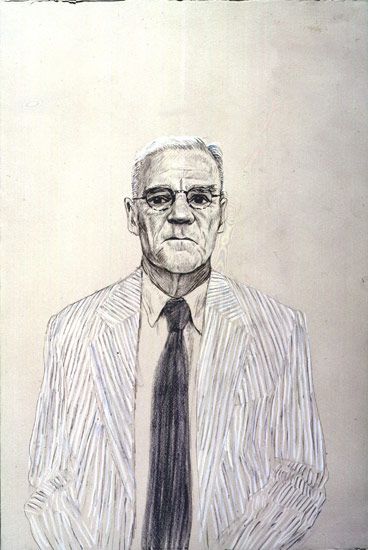

Captain Basil Hall (1788-1844)

British Naval Officer Basil Hall was—as experienced seamen were at the time—incredibly well traveled. Unlike most sailors, he kept journals throughout his career providing first hand accounts of distant explorations. When Hall entered the Royal Navy (at age fourteen), his father, noted scientist Sir James Hall, said "Now, you are fairly afloat in the world; you must begin to write a journal." He put a blank book and pen into young Basil's hands. Capt. Hall took his father's words seriously and throughout his navy career published accounts of his scientific, exploratory, and diplomatic missions. "A Voyage of Discovery to the Western Coast of Corea and the Great Loo-Choo Island in the Japan Sea" (1818) was the first description of Korea by a European. It was quite popular, and it secured Hall a high reputation as an explorer, scientist, and author. During his naval career, he would publish several books of his adventures, including "Extracts from a Journal written on the Coasts of Chili, Peru, and Mexico, in the years 1820, 1821, and 1822" (1823).

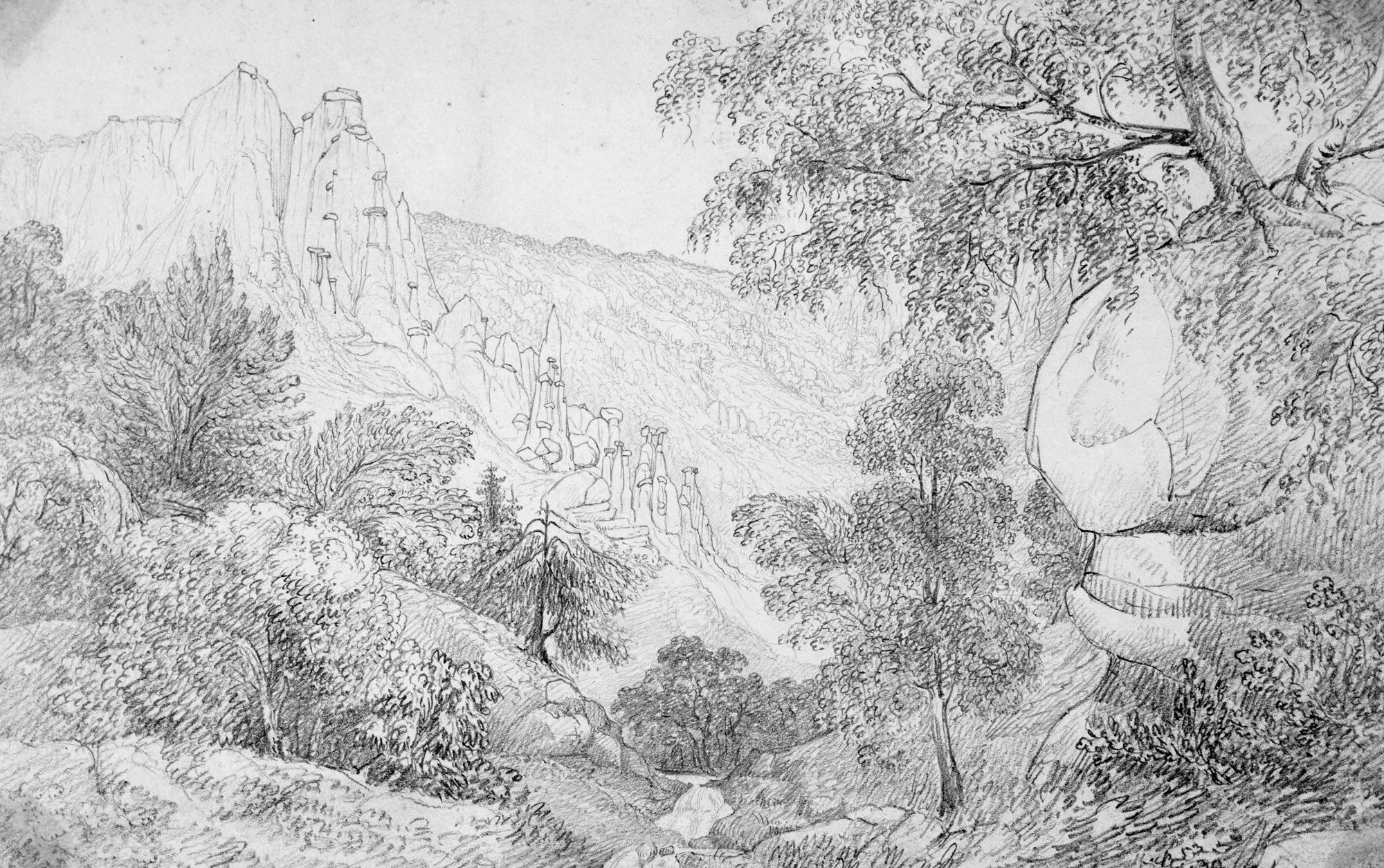

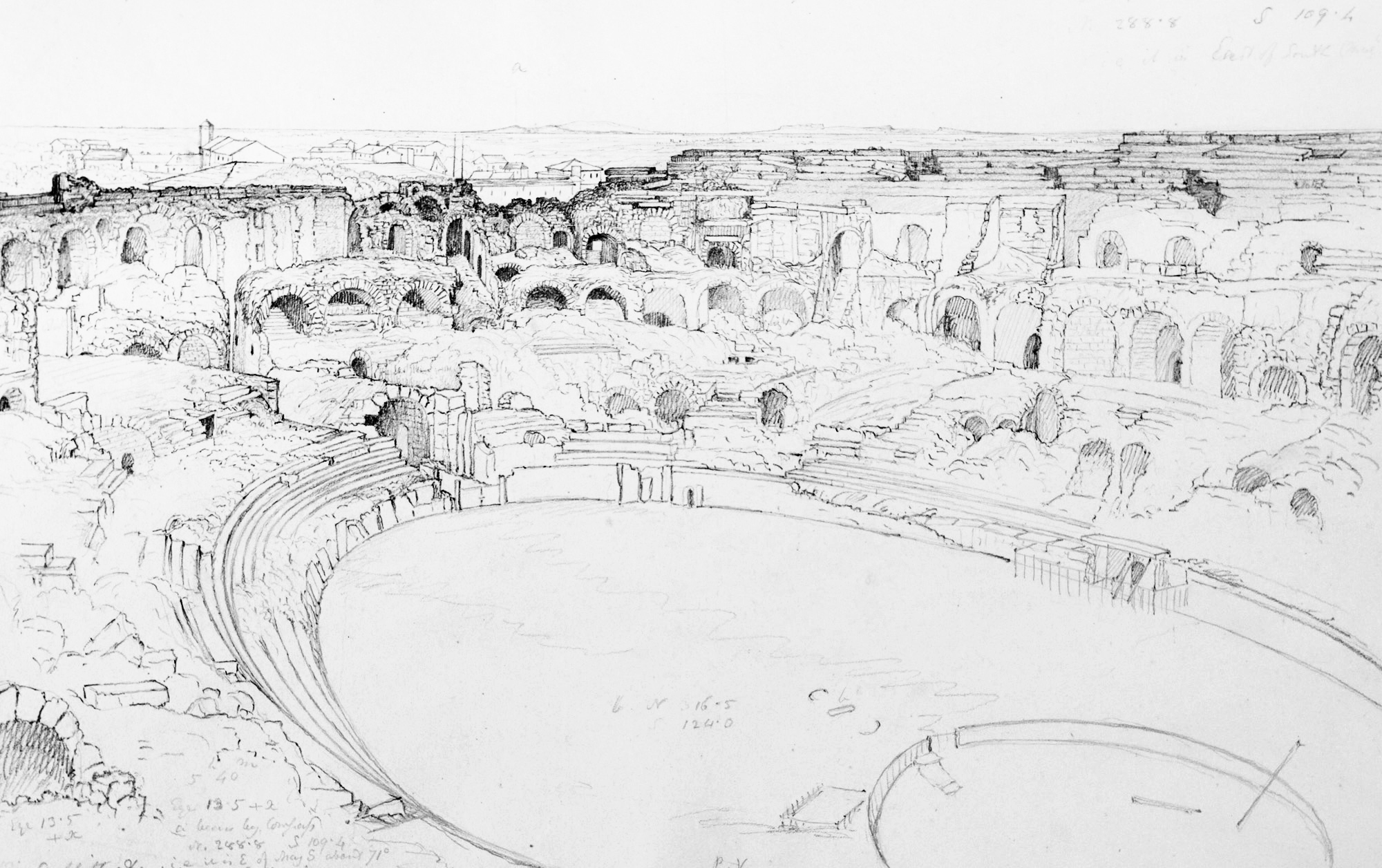

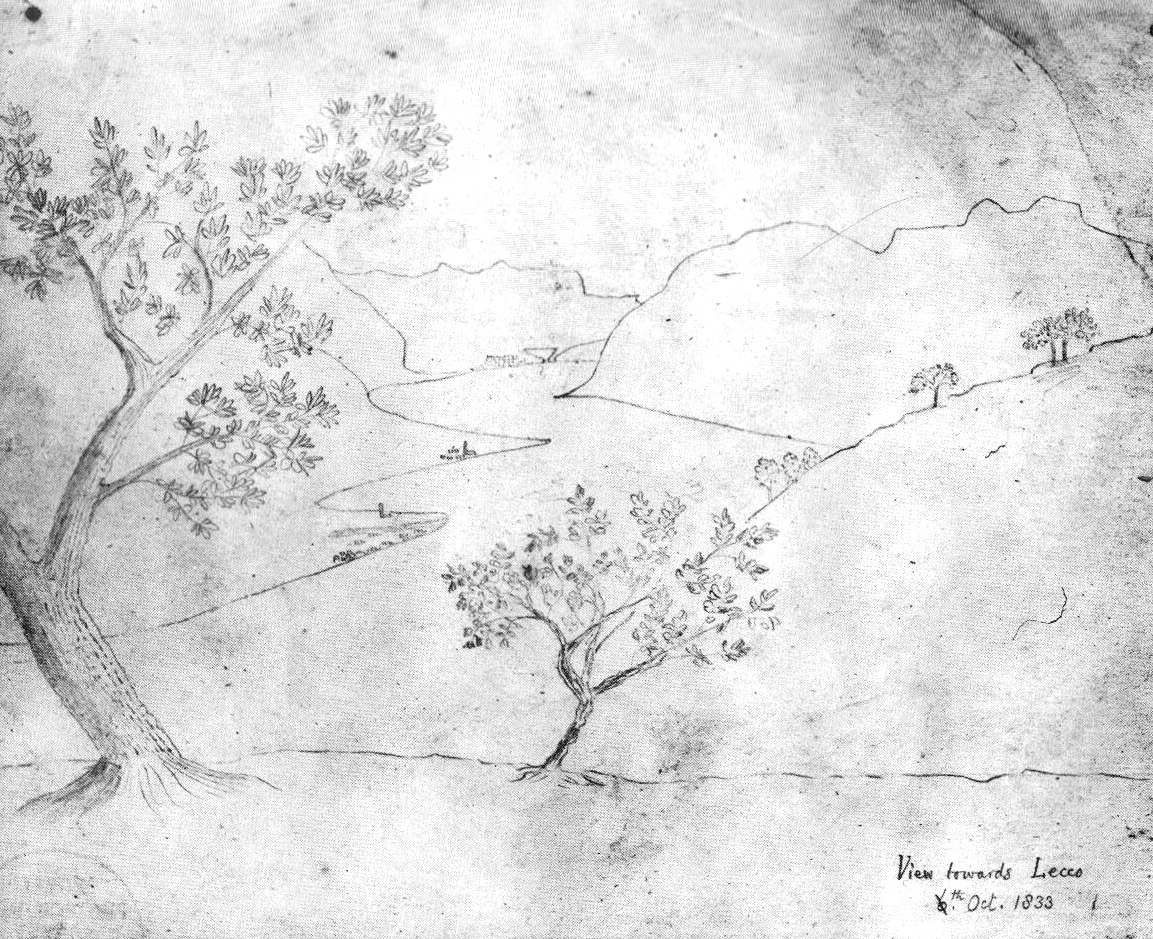

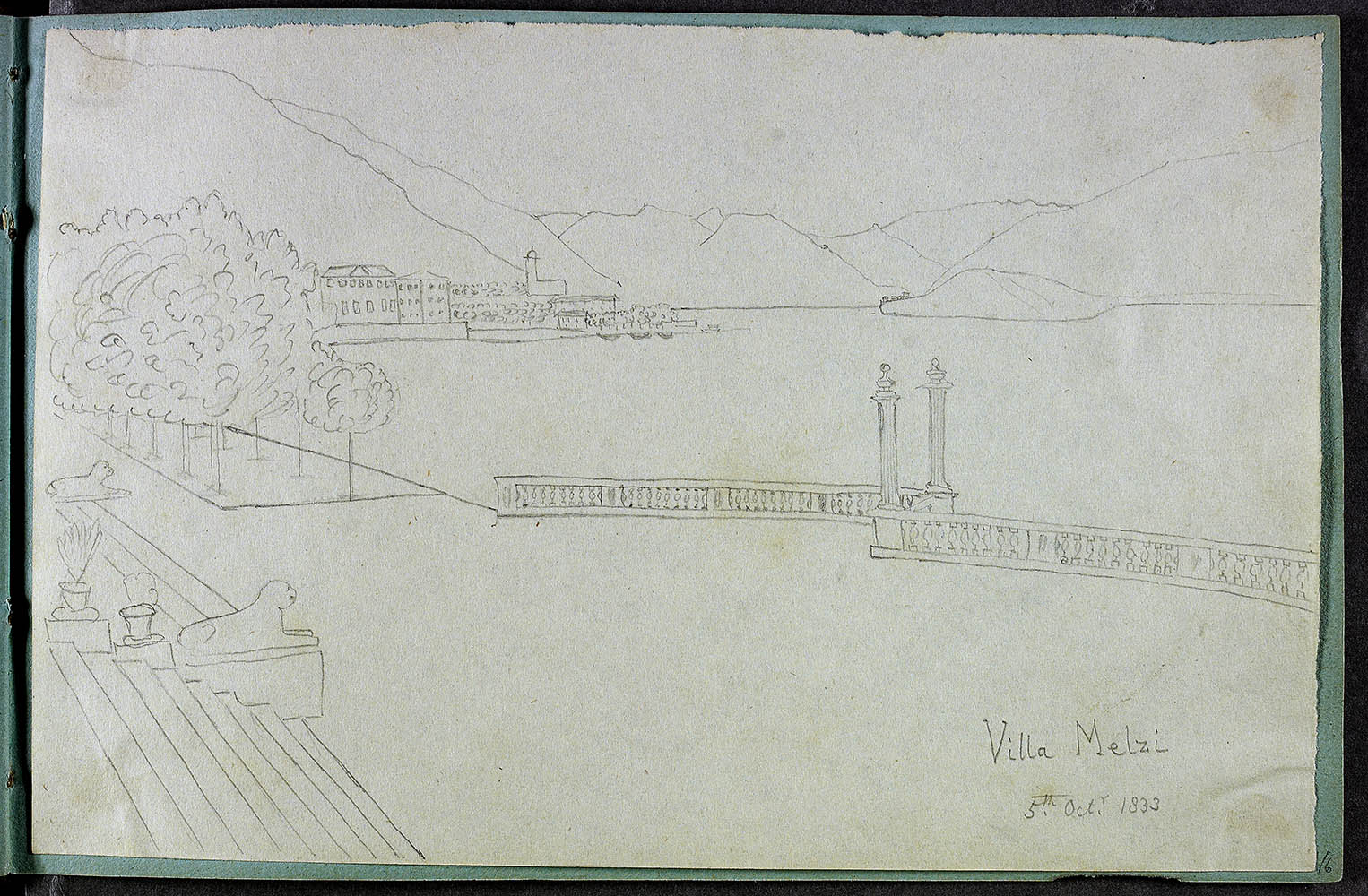

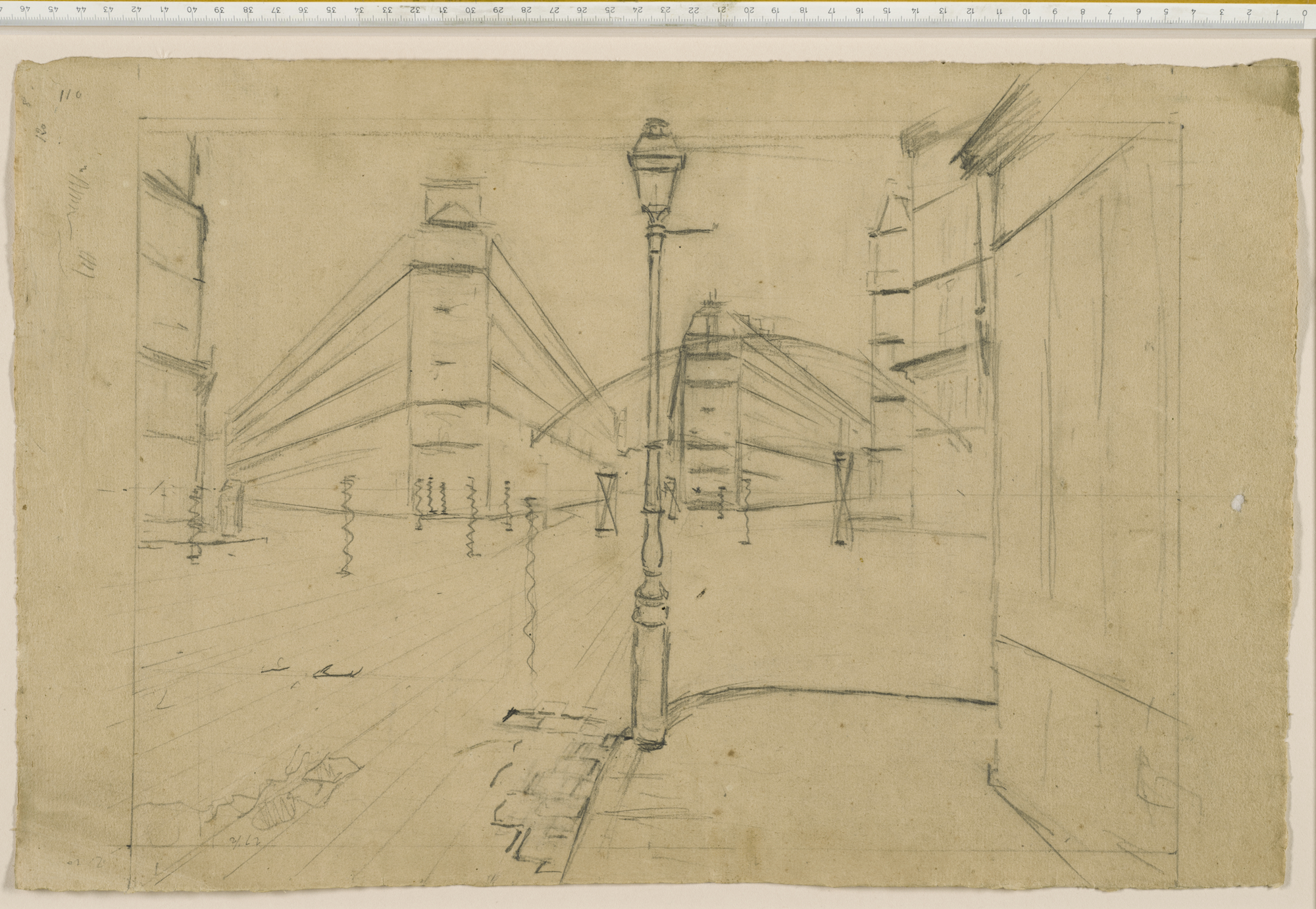

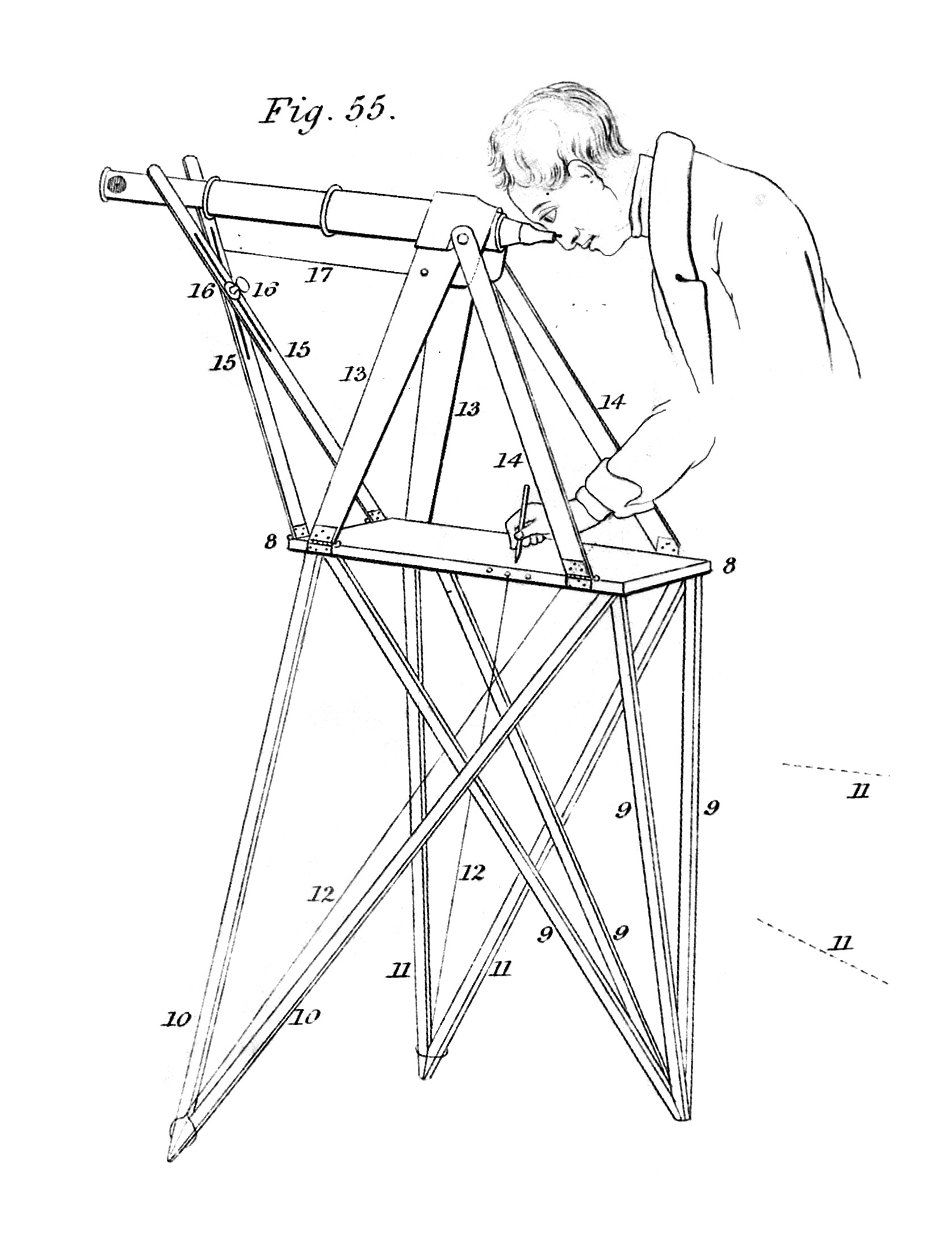

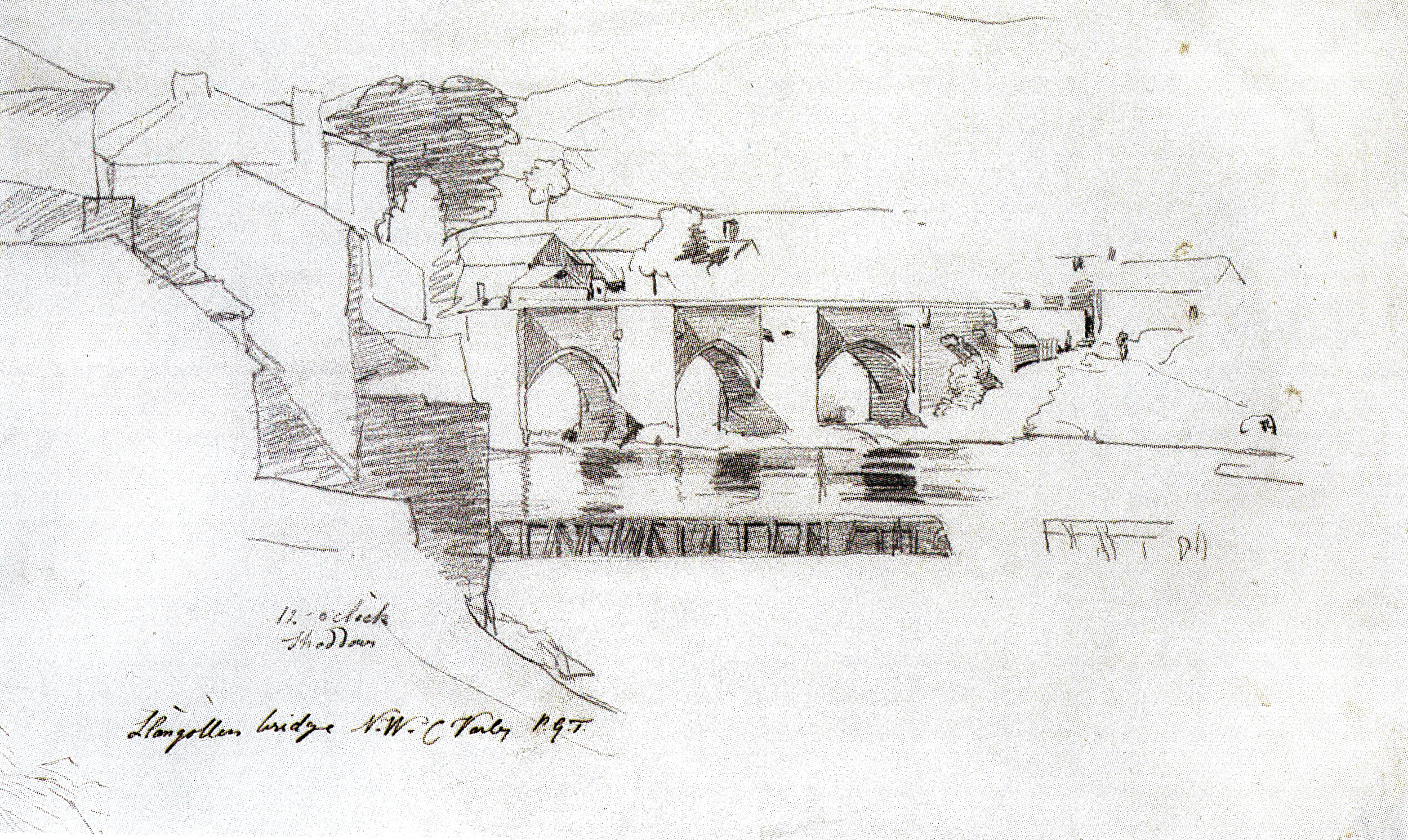

After retiring from service, Hall traveled to North America with a camera lucida and published accounts of his journey. The camera lucida provided the amateur draughtsman with an accurate way to depict the landscape, culture, and dress of the young America before the invention of photography. As an addendum to his three-volume "Travels in North America in the years 1827 and 1828" (1829), Hall published "Forty Etchings, from sketches made with the Camera Lucida, in North America, in 1827 and 1828" (1830). Forty of his camera lucida drawings and accompanying notes depict landscapes, city views, vernacular architecture, portraits of locals in regional dress, and even events like a forest fire.

Hall's devotion to the camera lucida was all about scientific accuracy. In the preface before the American Etchings, he writes: "This valuable instrument ought, perhaps, to be more generally used by travellers than it now is; for it enables a person of ordinary diligence to make correct outlines of many foreign scenes, to which he might not have leisure, or adequate skill, to do justice in the common way."